WORDS & PHOTOS by AIDAN MATTHEWS

Anyone who lives in Montreal or who has visited recently has likely seen one of Dan Climan’s paintings. His work is displayed across three billboards atop the RCA Building along the Ville-Marie Expressway, one of the main arteries into Montreal’s city center. Patrons of the eccentric Italian restaurant Gia Vin et Grill, which happens to neighbour the RCA Building, have seen his work hanging over the bar. And in Pizza Toni, a small slice shop in the Mile End, one of his paintings adorns the wall parallel to the restaurant’s four tables.

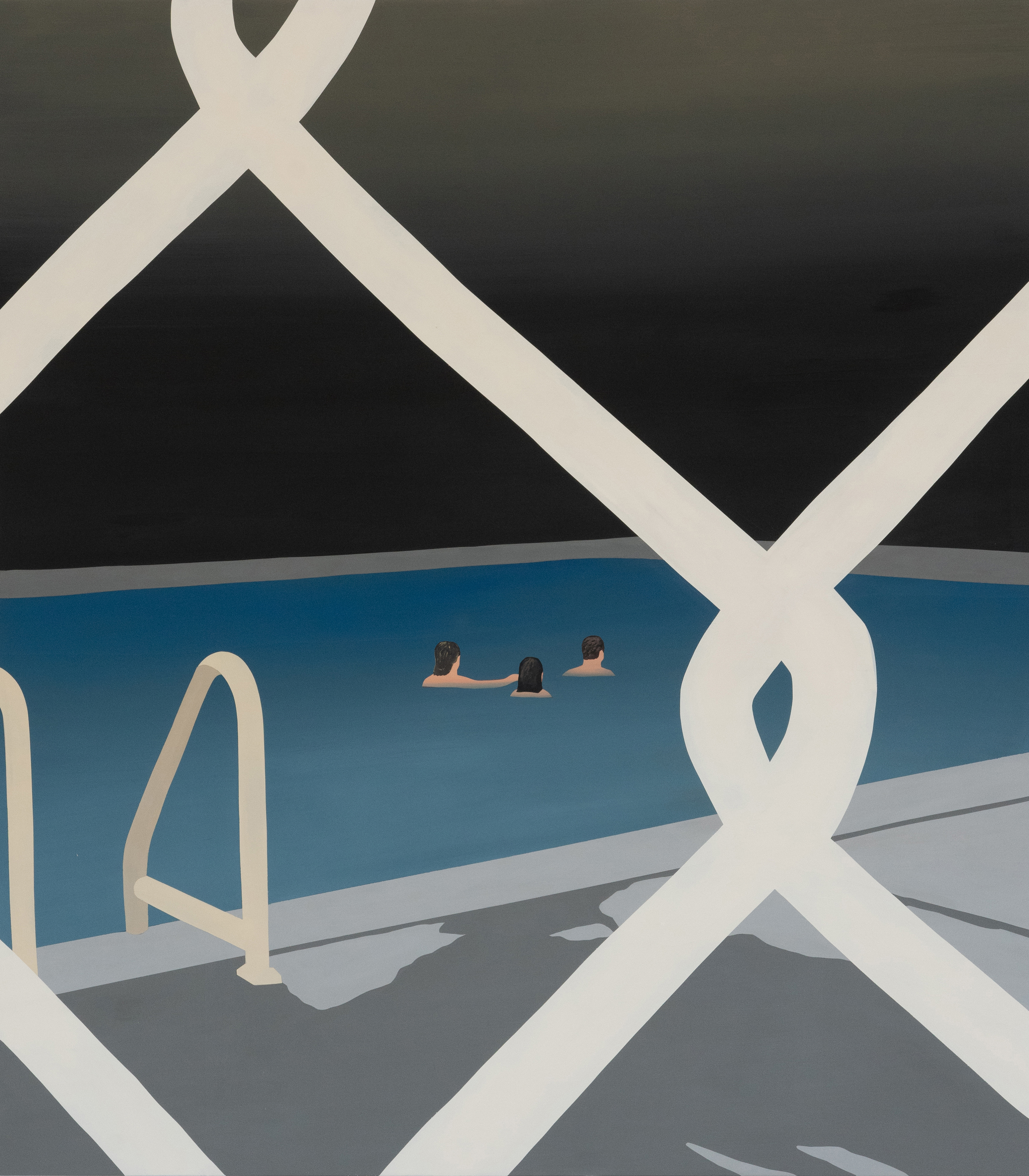

Climan’s work is unmistakable. It’s usually quite large, with precise edges and seemingly mundane subject matter rendered flatly in colours that could have been pulled from colour darkroom prints. In fact, when we spoke about his upcoming book, he pulled out Fred Herzog’s Modern Colour as a reference: “This is the best. All the colours of my paintings are in here.” Climan’s work reminds me a lot of Edward Hopper. The content is plain or minimal, but there is always something happening outside of the confines of the canvas. His paintings have prologues and epilogues but the viewer is left to come up with them on their own. The way he frames his often-lonely subjects is both unnerving and satisfying. Sometimes, the subject is seen through a window, or through the holes of a chain link fence. Other times, Climan imposes circular frames that connote binocular lenses. Like photography, Climan’s work relies on the act and the practice of seeing, but it also leans on the feeling of being seen.

We met Dan at his studio at the end of November to talk about how he has way too many photos on his phone, Instagram stories as reference material, when to stop, art school, making a living through art, restaurants, and his upcoming book with Wedge Studio.

Anyone who lives in Montreal or who has visited recently has likely seen one of Dan Climan’s paintings. His work is displayed across three billboards atop the RCA Building along the Ville-Marie Expressway, one of the main arteries into Montreal’s city center. Patrons of the eccentric Italian restaurant Gia Vin et Grill, which happens to neighbour the RCA Building, have seen his work hanging over the bar. And in Pizza Toni, a small slice shop in the Mile End, one of his paintings adorns the wall parallel to the restaurant’s four tables.

Climan’s work is unmistakable. It’s usually quite large, with precise edges and seemingly mundane subject matter rendered flatly in colours that could have been pulled from colour darkroom prints. In fact, when we spoke about his upcoming book, he pulled out Fred Herzog’s Modern Colour as a reference: “This is the best. All the colours of my paintings are in here.” Climan’s work reminds me a lot of Edward Hopper. The content is plain or minimal, but there is always something happening outside of the confines of the canvas. His paintings have prologues and epilogues but the viewer is left to come up with them on their own. The way he frames his often-lonely subjects is both unnerving and satisfying. Sometimes, the subject is seen through a window, or through the holes of a chain link fence. Other times, Climan imposes circular frames that connote binocular lenses. Like photography, Climan’s work relies on the act and the practice of seeing, but it also leans on the feeling of being seen.

We met Dan at his studio at the end of November to talk about how he has way too many photos on his phone, Instagram stories as reference material, when to stop, art school, making a living through art, restaurants, and his upcoming book with Wedge Studio.

AIDAN MATTHEWS - You have a background in tattooing and graphic design. Are these practices still part of your life?

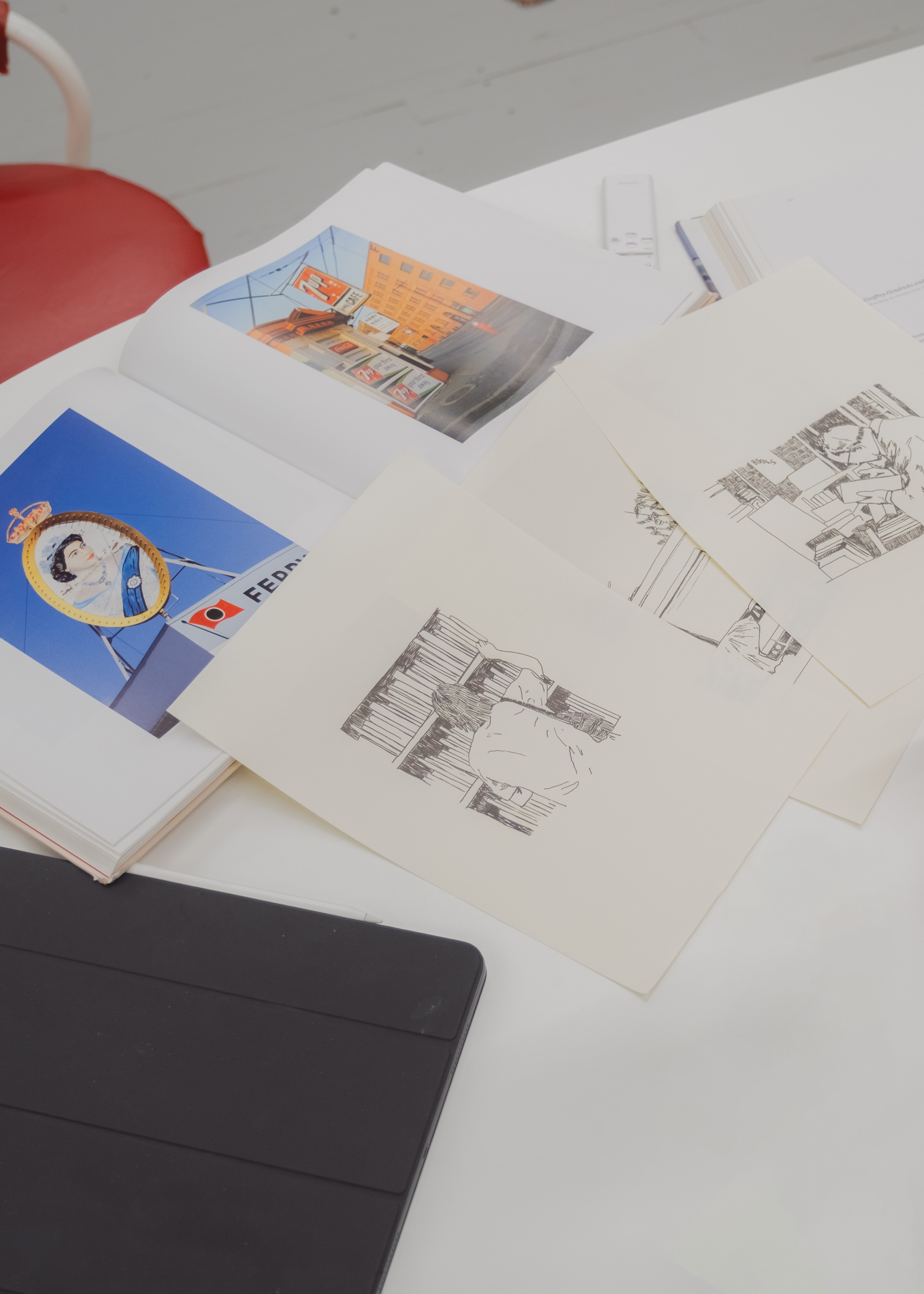

DAN CLIMAN - In university, my final work revolved around the re-appropriation of hand-painted signage. In Vancouver, I was interested in these mascots I would see like Mr. Mattress. I didn’t have a studio where I could use oil paint or 1 Shot, so I would paint them out of acrylic. I found a way to project the images and mask them, and I would cut shapes out of vinyl and paint following these stencils. It’s really similar to tattooing. Even now, my work starts with a drawing, and then I project it and mask it. I’ve always liked the idea of images that have a certain level of control. I like when the work feels tight. I think that has made my work appealing to people over the years. It looks a certain way for a reason. It’s not loose and flowy.

AM - There’s restraint.

DC - Yeah, big time.

AM - When you’re working on a painting, when do you know when to stop?

DC - I think I have a pretty good plan going into it. A painting starts with a sketch, usually of the most important part of the final painting. What’s going to change for me is the colours. Maybe I’ll make the sky a certain colour, and I’m like, “Wow, that’s the best colour ever.” But then I paint the car, and I’m like, “Fuck, the car looks so good but it doesn’t go with the sky anymore.” That’s when I’ll change the sky instead of changing the car. It’s a balance too. I'm always thinking about what involves more labour. I’m not going to re-cut all the shapes and fades of the car if I already like it, whereas the sky is just one shape. Over time, I’ve figured out how to pick and choose when to call it or what details to add.

My friend Ian Clelland comes in here and paints sometimes. When I was working on that one behind you, Follow, (we’ll be back again when it’s right), with the guy in the pickup truck, he suggested that I add a fade from the tire going onto the snow. I felt like there would be too many elements of visual push and pull if I did that. Part of the artistry is knowing when it’s gone too far, or knowing when it’s a little off. You’ll see that the tire on the left goes down lower than the tire on the right. That would drive some people crazy, but that’s what I want. I remember looking at paintings in my parents’ house and there’d be these perfect, almost symmetrical triangles and then one would be off. My whole childhood, I would wonder, why is that one not perfect? and it’s probably just because the artist did so many perfect ones that there’s some satisfaction in making one that’s off.

DAN CLIMAN - In university, my final work revolved around the re-appropriation of hand-painted signage. In Vancouver, I was interested in these mascots I would see like Mr. Mattress. I didn’t have a studio where I could use oil paint or 1 Shot, so I would paint them out of acrylic. I found a way to project the images and mask them, and I would cut shapes out of vinyl and paint following these stencils. It’s really similar to tattooing. Even now, my work starts with a drawing, and then I project it and mask it. I’ve always liked the idea of images that have a certain level of control. I like when the work feels tight. I think that has made my work appealing to people over the years. It looks a certain way for a reason. It’s not loose and flowy.

AM - There’s restraint.

DC - Yeah, big time.

AM - When you’re working on a painting, when do you know when to stop?

DC - I think I have a pretty good plan going into it. A painting starts with a sketch, usually of the most important part of the final painting. What’s going to change for me is the colours. Maybe I’ll make the sky a certain colour, and I’m like, “Wow, that’s the best colour ever.” But then I paint the car, and I’m like, “Fuck, the car looks so good but it doesn’t go with the sky anymore.” That’s when I’ll change the sky instead of changing the car. It’s a balance too. I'm always thinking about what involves more labour. I’m not going to re-cut all the shapes and fades of the car if I already like it, whereas the sky is just one shape. Over time, I’ve figured out how to pick and choose when to call it or what details to add.

My friend Ian Clelland comes in here and paints sometimes. When I was working on that one behind you, Follow, (we’ll be back again when it’s right), with the guy in the pickup truck, he suggested that I add a fade from the tire going onto the snow. I felt like there would be too many elements of visual push and pull if I did that. Part of the artistry is knowing when it’s gone too far, or knowing when it’s a little off. You’ll see that the tire on the left goes down lower than the tire on the right. That would drive some people crazy, but that’s what I want. I remember looking at paintings in my parents’ house and there’d be these perfect, almost symmetrical triangles and then one would be off. My whole childhood, I would wonder, why is that one not perfect? and it’s probably just because the artist did so many perfect ones that there’s some satisfaction in making one that’s off.

Dan Climan - Skip Intro (2022), Closer look (2022)

AM - Your work is realistic but it’s not hyperrealistic. So if you start adding realistic details, it gets away from the original feeling of what you’re trying to show, and becomes more of a record.

DC - Totally. There’s also this push and pull between photography and cinema. I don’t want it to look like a photo because photos are capturing something close to what your eye sees. Cinema is capturing a fake version of what your eyes see. A painting can be whatever you want. I’m capturing whatever I’m seeing. You’re in my studio now and you can see there’s a certain sense of order, and I need that to feel comfortable. My work is an extension of me and my own feelings. As much as the content is trucks, people, landscapes, vanishing points, and space, there’s still an aesthetic of cleanliness, and that makes me feel good. I think people connect with my work because they feel like they want to live with it. They feel like it would be nice to have around. And that comes in both ways. Sometimes, something is so chaotic, which makes it special. Your brain can bounce around the canvas and you can’t stop looking at it. But also, when something is so simple, it can feel nice.

AM - You said that a lot of your paintings have some sort of narrative, but they’re incomplete. We don’t know what happens next. There’s always more to it but we don’t see it.

DC - A lot of them spawn from memory. Or, you see an image or a screenshot, or something in a film that triggers a memory. It’s like something you did when you were twenty years old that sort of stands out in your mind. You remember parts of it, but you don’t remember the whole day or what came next, or what you were feeling. [My work] is based on visual memories. Coming from Quebec and going out West, going to the Interior, going to hot springs with my buddies who had trucks, I remember the vastness of the space and getting there and getting back, but there are still a lot of unknowns.

AM - How do you mediate commercial and personal work? Can they exist together?

DC - There’s a couple things. I give value to my work by consistently giving it time and energy. The harder I work, the more I want back. So if I’m painting all the time, I want to have a nicer studio so that when people come to experience the paintings that I’ve worked hard on, they have a nice space to enjoy them within. Even the panels I work on are really beautiful panels that are handmade by Zeke at Faux Cadres Canal. So before I go into a painting, there’s already this element of noble materials. A lot of my paints and my tapes are Japanese. I’m nervous before going into a painting because so much goes into preparing to make it.

The commercial success comes from work. I’m not looking to put in a little bit of work and get back a lot of success. I don’t see my paintings as a product. I don’t take commissions. I just paint what I want to paint.

AM - Has that reverence for materials always been important to you?

DC - I think it was in tattooing because you’d always want to work with the best machines or the best ink. It was kind of like insider trading because you’d go work in a guest spot and you’d ask the other artist about what they were doing. There were little secrets that you would gain access to because you were interested enough to travel to another city to work with another artist. But there’s two worlds. A lot of people can make beautiful work on the cheapest materials in the world. But for what I want to do, because it’s so calculated, I want to make my work on really beautiful materials.

AM - How did you get into working with restaurants in Montreal? How does that kind of work tie into your practice?

DC - Oh man, I’ve done so much branding. I did Matty’s Patty’s in Toronto with Matty Matheson. I did Rizzo’s House of Parm. Until a few years ago, I was the creative director for Artist World at Osheaga. I helped with creative direction at Joe Beef. I did an illustration for Elena that’s in the pizza boxes. I worked on Mano Cornuto. I love restaurant merch and I love that era of design where it’s really repetitive. It’s a mascot, a bold font, primary colours, and the variation doesn’t change that much. In a general sense, this is what I do [in my practice]. I like traditional tattooing; I like eagles and daggers and snakes. They’re all in this similar vocabulary but there’s subtle differences. Even in my paintings, the themes and the way they’re set up kind of exist throughout my work. It’s just how my brain works.

AM - You have motifs. You’ve sort of replaced the mascots or the traditional tattoo figures with cars, dogs, and landscapes.

DC - Yeah, but with paintings I get to think about those things way more. Going back to pushing away from the academic side of things in university, now I want to think about what I’m doing.

AM - You were telling me you partnered with Danny [Smiles] on his new project in the former Maison Publique locale.

DC - Yeah, it’s really exciting because I get to be involved in designing the space, and designing all the branding and merchandized objects that we’ll have. In the past, I’d do graphic design [for a restaurant] and then step away because I didn’t have the time to keep up with it. It would always get away from me a little bit, whereas this project is mine. The restaurant will look exactly how I want it to look. Since I’m a partner, this will just be an ongoing project that will become a part of my life.

AM - What do you look for in a restaurant?

DC - I really like classic. I love L’Express. I love the experience of being in the room because it doesn’t feel like Montreal. You feel like you’re in Paris thirty years ago. The food is always great. But I also like when the staff is warm, and people go out of their way to make you feel like they’re happy that you’re there. Mon Lapin is amazing. Pichai is amazing; it has maybe the most interesting flavour profiles in the city. Maison Publique used to be one of my favourite places to eat. Derek [Dammann] can make like three ingredients taste incredible. But I also love going to the Orange Julep because I know there’ll be some characters in line and I’ll get to eavesdrop on a story. I’m going to get that infamous cup. Everytime I see that Gibeau Orange Julep sign with the neon lights, I feel good and I’m reminded that stuff doesn’t look like that anymore.

AM - How did you learn how to be a professional artist? Did your time at Emily Carr teach you anything about working as an artist? Or did it mostly come from working and learning on your own?

DC - I think I was so young at Emily Carr and so I had these delusions of grandeur like, nothing really happens in school, and once school is done, then life starts. So, I kind of just ripped through university and didn’t take into account that I had so many good resources available to me. I look back at my teachers and I’m like, you’re a famous, amazing artist. I love the work you do. You curated a huge show at a huge gallery. You know every single person I’m trying to meet in my career now. They were right there at my fingertips. But we’ve always had good relationships on a human level. I was never the kid who was putting in the most work. I was good at making stuff that was good enough to do well in art school, but my head just wasn’t in the game yet.

I was watching a documentary on Ed Ruscha and he talks about how he basically never did anything he didn’t want to do. He hand painted signs at department stores when he was a teenager, and I feel like I can fully relate to that mode of creating. I never wanted to have a job where someone told me what to do. That’s sort of what snowballed me into graphic design and tattooing and making party flyers. I wanted to get paid and afford to do the stuff that I wanted to do. I wanted to do it my way. I wasn’t thinking about it in the most academic way because at that age, that’s not how my brain functioned. But I liked drawing and being on top of pop culture, so I had to figure out how to make that work. I feel like that’s a skill in itself.

Dan Climan - Billboard Installation (2021 - present) photo by Alexi Hobbs

Dan Climan - Billboard Installation (2021 - present) photo by Alexi Hobbs

AM - I see your billboard installation a few times a week. How did that come to fruition?

DC - During the pandemic, my studio was in the RCA Building. Ryan [Gray] and Marley [Sniatowsky] were building Gia, which used to be the old garage for the snow plows that cleared the parking lot of the RCA Building. The building manager was this guy Andrew Rankin and he used to come see us. We went to high school together. Pattison’s lease on the signs on top of the RCA ended during the pandemic so there were two options: take the signs off the roof completely, or give the signs to Allied (the real estate company). But, Allied doesn’t believe in advertising so when I got wind of the situation, I spoke to Andrew.

My original idea was to curate the sign as a floating gallery in the middle of Montreal’s cityscape. Ultimately, I already had those pieces ready and because they have these calm settings, my art is pretty digestible, so it couldn’t really offend anyone. I get emails from people saying they drive past it every day, and that when they have a bad day, seeing the billboards sort of cheers them up. I think that’s so sick. I love an art project where I get to hear about what people feel on different days when they encounter it.

Also, one side is a night scene and the other side is a day scene. So when you drive into the city, you see the day side, and when you leave, you see the night side.

AM - What can you tell us about the book you have coming out?

DC - I’m putting out a book with Wedge Studio, which hopefully comes out in January. It’s basically a retrospective of the last three years of paintings. With the amount of attention I get for my work online, I feel like most people are experiencing my work on their little screens where everything looks so digitized, so I really wanted to make a book. You get to see the textures and all the details.

AM - How did you go about sequencing all the work in the book?

DC - I let Wedge figure out the sequencing because I don’t really have a reason for what I’m making or when I’m making it. I’ll go minimal and then be like, “Oh, it’s too minimal, I need to get maximal!” Or, I’ll paint a landscape and then feel the need to paint a person. That’s just how it goes. I’m searching for this feeling. I didn’t want to organize it chronologically or by subject matter, so I let them just lay it out.

AM - What do you get out of your work?

DC - I have a toolbox to make images. Like I said, I have this system of masking and cutting and doing fades. I’m always feeding the fire that tells me that something is worthy of being turned into a painting. Even nowadays on Instagram, I see people’s stories all the time and they’re like references that only last 24 hours. I screenshot other people’s really candid, shitty photos. They don’t know that maybe the top right corner of their picture just really got me going. There’s a vocabulary in my head and it’s always talking. There’s an excitement to following that voice, and hearing it say, “This is really good; you’re onto something.” And then halfway through, you’re like, “This is shit. This is the worst thing ever.” I paint over things all the time.

AM - What do you want people to get out of your work?

DC - I paint for me, but I also know that I’m painting because I want other people to enjoy it. I want people to really feel from the work. Each piece isn’t the most in-depth story. I’m stepping away from the fact that everyone is going to have a different connection to the work. What’s been nice about working on the book is that I’ve had distance from paintings I did three years ago and seeing them now, I’m like, “Fuck, these are good!” If I’m having that experience, I’m curious about someone who owns the work. How do you feel about the work after three years? Does it mean more to you? Does it mean less to you?

People tell me that my work reminds them of Alex Colville or Alex Katz. I challenged myself to make a painting that sort of had a Colville colour palette, just to see what it would look like. In the end, I almost see less Alex Colville in the painting, and more of my own style.

DC - I have a toolbox to make images. Like I said, I have this system of masking and cutting and doing fades. I’m always feeding the fire that tells me that something is worthy of being turned into a painting. Even nowadays on Instagram, I see people’s stories all the time and they’re like references that only last 24 hours. I screenshot other people’s really candid, shitty photos. They don’t know that maybe the top right corner of their picture just really got me going. There’s a vocabulary in my head and it’s always talking. There’s an excitement to following that voice, and hearing it say, “This is really good; you’re onto something.” And then halfway through, you’re like, “This is shit. This is the worst thing ever.” I paint over things all the time.

AM - What do you want people to get out of your work?

DC - I paint for me, but I also know that I’m painting because I want other people to enjoy it. I want people to really feel from the work. Each piece isn’t the most in-depth story. I’m stepping away from the fact that everyone is going to have a different connection to the work. What’s been nice about working on the book is that I’ve had distance from paintings I did three years ago and seeing them now, I’m like, “Fuck, these are good!” If I’m having that experience, I’m curious about someone who owns the work. How do you feel about the work after three years? Does it mean more to you? Does it mean less to you?

People tell me that my work reminds them of Alex Colville or Alex Katz. I challenged myself to make a painting that sort of had a Colville colour palette, just to see what it would look like. In the end, I almost see less Alex Colville in the painting, and more of my own style.

Dan Climan - Rite of passage (2023), Follow (we'll be back when it's right) (2023)

Dan Climan - Rite of passage (2023), Follow (we'll be back when it's right) (2023)

AM - That’s exciting, right? Getting away from my references is something I’ve struggled with as a photographer. The more you work on something, the further away from the reference you get. That’s a satisfying thing.

DC - Yeah, totally. I paint like six days a week. I get better. Even at thirty-six years old, every month, I get better. Gerhard Richter stopped painting this year, at ninety years old, because he felt like he wasn’t getting better anymore.

I love Alex Katz’s work. But more than anything, I love listening to him talk about his work. Him and Peter Doig. Even Ed Ruscha. I’m now working on that aspect of my art practice. Apart from just making nice paintings, I want to be able to explain where my thought process comes from. When you listen to someone who has spent fifty years painting, they’ve narrowed it down. The way they talk about their work is as efficient and as good as the images they’re making. But that takes time! I could never explain why I wanted to make anything when I was in art school. And now, no one is asking why I’m making something to give me a grade, but I want to be able to answer the question for myself.

AM - So you’re in here six days a week?

DC - Yeah, pretty much. Painting, sometimes I’m drawing or prepping, getting things organized.

AM - How much time do you spend doing research?

DC - I live the work. I know that sounds super corny, but anytime I’m at home and watching a movie, I’m taking iPhone photos of the TV. “When I’m driving, I’ll get my girlfriend to take pictures of things.”

AM - Your research is really instinctual and then you take time to sort through things after.

DC - Yeah. Sometimes I miss the photo so I’ll scour the internet trying to find an image that matches what I saw. I try to look at references in books more than anything. But there are so many intricate little things in photos that can be turned into paintings. Sometimes I feel like when you take a specific reference image from the Internet, there’s still the sense that it’s a bit too close or a bit too easy. But I like stealing Instagram stories. I think it’s funny, and I’m sure one day, someone will realize that I took their story and used the corner of it in a painting. Every phone I have has like 13,000 photos on it, and they just get transferred from one phone to the next. If you look in my phone now, it’s fucked. My screenshot album is 9000 photos.

Watch out for Dan’s upcoming book in early 2024

and follow his work here.

www.dancliman.com